Ever since “Charlie Victor Romeo” took off at the Sundance Film Fest earlier this year, the filmmakers have been doing a fair amount of travel, something you might think they’d be loathe after spending the past decade poring over the details of plane crashes to create a most unusual theatrical experience.

“When you fly home and you land, you see [the flight crew and] they’re all like “Thank you. See you” when you get off the plane,” says co-director Robert Berger. “When you look at them, I feel so much better about flying. I’m the one always like, ‘Thank you so much!’”

It’s a feeling that’s likely to resonate with many audience members after seeing “Charlie Victor Romeo,” a film that utilizes the transcripts from the black box recordings of six downed airliners to reveal how the respective flight crews handled the moments of crisis.

Far from the lurid exercise this might seem from the premise, Berger and co-directors Patrick Daniels and Karlyn Michelson instead find the unexpected grace and resolve in the interaction between the doomed pilots who do all they can to avoid crashing physically while keeping they keep each other mentally at ease with their banter, at times by being completely engaged in technical discussions or at others by lightening the mood with jokes or small talk.

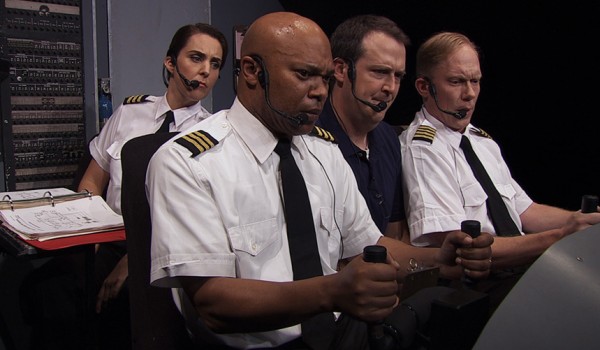

Despite an initial barrier of technical jargon in the crew’s contact with their air traffic controllers, such a window into the pilots’ cabin during their brush with mortality pulls an audience closer to the humanity of these men and women, a quality that’s enhanced by the film’s use of 3D and oddly enough, “Charlie Victor Romeo”’s unapologetically low budget, which paid for a simple set and a septet of actors (including the three directors) to bring the transcripts to life and all but removes artifice from the equation.

Not that there weren’t offers to turn the project, which started life as a stage production at the New York-based Collective: Unconscious Theater in 1999, into a larger-scale film. Yet the Collective’s demand for creative control took them down a different path, one that not only led to them to make their own film but one that has since been embraced by the aviation community as a potential training tool. While in Los Angeles recently for AFI Fest, Berger and Daniels spoke about the 14-year development of “Charlie Victor Romeo” from the stage to the screen, why 3D was an important element to make it more realistic and filling in what the transcripts left out.

With that passage of time, does this means something different to you now than when you first put it together?

Robert Berger: Oh, God!

Patrick Daniels: Of course. It’s interesting, as we’re aging, I’m finding myself in maybe a more spiritual place. All of my life experience is deepening. Having started out as a director and performer on [“Charlie Victor Romeo”] live on stage and bringing it to this place, it’s obvious to me that things have a life, in general, and it’s really important to acknowledge that. People don’t get to work on stuff as long as they should sometimes. It’s been key for my own personal experience of this that we’ve been able to actually continue to address it and correct it and refine it and reduce it to its core and really, as much as possible, try to perfect what the object is.

Robert Berger: And to perfect ourselves. As a filmmaker, what I might have thought would have been the right thing to do in 2000, or my ability to execute that is vastly improved. By the time we decided to do this [as a film], there was no question as to could we do this? It was like, “No, we can totally do this right now.” There was a crazy reach exceeding grasp aspect of this whole piece of art. We’re going make a play. It’s going to be about reconstructing aviation emergencies from cockpit voice recorder transcripts, and we’re going to do it live onstage, and we’re going to have this surround sound environment in a 50-seat theater. [That became], “Let’s shoot the movie. We’re going to do it live, of course and we have to do this multi-track recording of the audio and let’s do it in 3D.”

Patrick Daniels: A lot of questions got asked and answered by us to ourselves over time. The actual production was shot over three days of live performance, but the same people that you saw in the film have been working on the play for years, off and on. It’s not a full-time job by any means, but certainly the refining of the object made it actually pretty easy to answer the technical production-style questions that we had before we actually did the shooting.

One of the interesting things about your use of 3D in particular is that typically it seems what’s onscreen is coming to you, but here it feels like you are drawn in. How did you worked out that spatial relationship?

Robert Berger: In stereoscopy, every time something pops out of the screen at you, you are affecting the optics of your brain in a particular way. You will never be able to lie on the couch and watch a 3D TV that’s filled with images coming out at you. That’s what gives you a headache. Breaking that plane of convergence is what makes you feel uncomfortable when you are watching 3D. The thing about “Avatar” that blew my mind was not the “coming at you” effects, or even necessarily the things drawing you in, but it was the particle effects that were in the environments after fires and ashes are drifting down. You feel like they are all coming down all around you.

Our goal using 3D was basically to increase intimacy between you and the performers, putting this on in your lap just the way it is theater when we do this live. We want you to feel like you’re sitting right next to these people and having this experience right in front of you.

Patrick Daniels: A filmmaker friend of mine who saw the film yesterday, said that he was able to relax and trust not only the pilots in the circumstances, but trusting the filmmakers and the actors that he wasn’t going to be led astray. He didn’t say this specifically, but I think it has to do with the way 3D is being used in this and [how] the brain perceives things. I think of this as a softer experience of 3D. It activates your brain.

Robert Berger: 3D is never used to tell a story. It’s never used for dramatic purposes. It’s used for effect. The conventions of film are so expected. We expect that this is what a frame looks like. We expect that these are the standard shots, this is what a person looks like, this is how you color correct — all of that stuff, and we have this expectation about how film looks. But when you tell a story that’s 3D that’s not specifically like, “Hey look at this!”, how does that affect the way the audience perceives the story?

Yes, this is a piece of theater and so on, the performances, the acting and the characters and what’s going on is so powerful, but can we put the audience in a place where we’re manipulating where their head is at? Are they in an airplane? Are they in a theater? My favorite quote about this was from a filmmaker friend of mine who made a cross [reference] between [Neil Young and Crazy Horse’s] “Rust Never Sleeps,” which was a concert film, but you really can’t see the audience and it’s also [Alfred Hitchcock’s] “Lifeboat” — you can’t get out of the boat. We really wanted to play with that and experiment with where the audience’s head is at.

But it’s not honorable to approach this text and use this text for entertainment purposes. It’s specifically the result of an investigation and it’s published to the public because people need to be educated. All along, we’ve been working on that. It involves the curation of work and making sure that we are at least maintaining our provenance over this thing in a way that we are trying to maintain our respect for the material. The more powerful it is, the more I want it to be obvious that this is our attempt to bring these events to life in a way that does not focus on the personalities or the histories of the people involved, but rather on the power of what they did and that experience for every man.

There are obviously nonverbal moments in the film, such as when a pilot checks out a flight attendant in the film’s second segment, that couldn’t have come from the transcripts. What was it like to fill in those ellipses?

Patrick Daniels: Various iterations of the script are actually just the transcripts pulled out of the NTSB investigation document, but when you read the transcripts, there’s this time code and the time code jumps because they edit out the parts that aren’t pertaining to their investigation. Profanity is indicated as a hash tag perhaps. There’s all this weird punctuation that’s specific to the way they produce this stuff.

Robert Berger: Explicative redaction.

Patrick Daniels: It shows you that something was going on. When you’re working on Chekhov or Shakespeare, you’re trying to figure out the subtext and when you’re working on this, that subtext is as present as it is in anything. One of the things that comes about as performers through our investigation of this stuff is that everybody does it differently, but there is also a similarity. I played a bunch of different parts in this. Other people played some of the parts that I have and there is as easily as much similarity in what different folks do with it as there is difference.

Robert Berger: If you take a text like this, and we’ve artistically canonized these texts working on it for so long, the work of interpreting these texts, like scripture or Shakespeare, is really strange because you have to understand what [is being said] and how to say it and not sound like you don’t know what you’re talking about. That’s the training required to perform.

[In that] moment before the airplane that you’ve been struggling with for 40 minutes that you’re attempting to bring it to a successful landing and the tower says that you’re clear to land on any runway, you say, “You want to be particular and make it a runway, huh?” The actual person said that joke. The effect of that joke on the other people on the flight deck was incredible. What an incredible, amazing thing to say; to joke in the face of what’s about to happen, and how you tell that joke, and how you sound, is actor’s choice. It’s curated by directors, but we want that interpretation. We don’t want it to be the same; we want you to feel it. It feels real. If it feels real, then it’s right.

Patrick Daniels: I had an acting teacher in college who used to always say it’s a struggle to learn how to be realistic on stage regardless of the material. She said over and over in our class, “You know when you are in the presence of real emotion.” That’s 20 years ago and change, but that stuck with me forever. As a performer, when you notice those moments, you reach for them and try and hold on to them as tightly as you can and keep it going.

“Charlie Victor Romeo” will be released in 2014.